South Korea’s National Election Commission (NEC) is under heavy scrutiny over its performance in overseeing the April 15 General Election earlier in April. The 21st National Assembly is set to do its legislative work, yet the controversy persists about the electoral anomalies.

The election has produced a supermajority for the ruling Deobureo Minjoo Party (DMP). The DMP members should have been ecstatic that they had won a commanding victory, 180 seats out of the 300-seat Assembly. However, on the night of the election, they appeared as if they were in a funeral parlor rather than a victorious hall. In the live broadcast with the DMP leaders seated in the front of the hall, the public saw only subdued cheering, causing many to raise their eyebrows about the odd behavior the DMP brain trust had displayed.

They should have been jumping and clapping, but they did not. Why not?

That was the first of the many questions to follow. Two months later, the National Election Commission (NEC) is still unable to explain a host of questions that had been raised. Many civic organizations have brought dozens of legal complaints against the NEC regarding electoral anomalies, many of which have to deal with the preservation of ballots, servers, and electronic equipment.

One of the main questions is: Why did the NEC use the a QR Code on the absentee (early-voting) ballots explicitly barred by law (Korean Election Rules Article 151)?

Rather than offering explanations, the NEC adopted a hostile attitude toward the questioners, causing ire among the public. The NEC ’s behavior is very perplexing: Instead of building confidence among the electorate, it is creating more doubt about the electoral process it had overseen.

As it turns out, the NEC’s questionable behavior goes back to 2013, when it established the Association of World Election Bodies (A-WEB) in Songdo, South Korea. The NEC’s charter states it is “an independent constitutional body tasked with managing elections and affairs related to political parties and funds.”

Curiously, it was involved in developing and exporting electronic election equipment with an enterprise called “Miru Systems” (Miru), according to Skyedaily internet newspaper in South Korea. The government entity is not supposed to be involved in commerce, but evidence shows that it had colluded with Miru to export election equipment around the world.

Skyedaily has done anextensive investigation into the issues surrounding the syndicate consisting of Miru, NEC, and A-WEB. Together, the group has engaged in untoward activities with global implications.

Looking at the relationship between these entities, conflicts of interest are evident at every turn, which will be explained in detail later. For now, here are some salient facts about the complex system:

· NEC receives its budget from the South Korean National Assembly.

· NEC finances A-WEB with the membership of about 110 nations.

· National Assembly approved budgets in 2017 and 2018 for NEC to “Spread Korean election system overseas.”

· NEC authorized Miru as a supplier for electronic election equipment for A-WEB member nations.

· Miru nearly monopolized the supply of electronic election equipment to A-WEB member nations.

· A-WEB awarded supply contracts to member nations not by open competition but contract ad libitum with Miru.

· Miru supplied to A-WEB member nations: Ecuador, El Salvador, Dominican Republic, Kirgizstan, and Democratic Republic of the Congo.

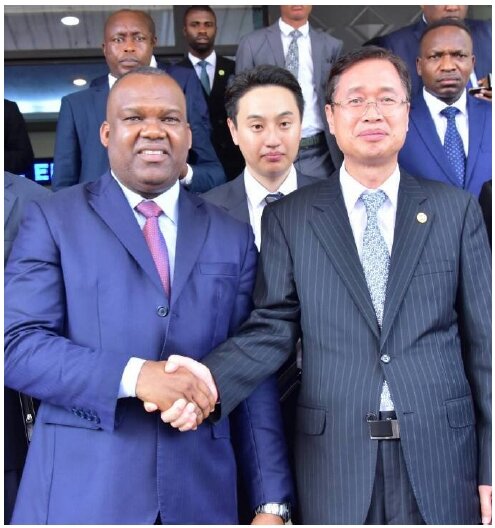

In 2018, the Democratic Republic of the Congo held a presidential election for which Miru was awarded a contract to supply electronic voting machines. When the contract award was announced, a number of experts issued warnings about the electronic voting system.

The Washington DC-based Center for Democracy & Technology chief technologist Joseph Lorenzo Hall identified the technology’s potential vulnerabilities. This included potential threats to ballot secrecy and vulnerabilities to hacking based on his prior experience with QR code technology.

According to Hall, “QR codes may store more information than simply a voter’s ballot selection, potentially including the time a person voted, their place in line and other voter-specific or ballot-specific identifiers. This information can be used to correlate the contents of a ballot to a specific a voter’s identity, violating ballot secrecy. According to Hall, electoral authorities must take steps to ensure that ballots cannot be recorded, photographed or viewed by anyone other than the voter. Without proper controls, nefarious actors could exploit actual or perceived threats to ballot secrecy to intimidate or discourage voters. For example, a political party leader could tell voters they will take note of who cast a ballot for which candidate, threatening consequences for dissenting voices. Even perceived threats to ballot secrecy could result in a chilling effect, suppressing voter turnout.

Hall pointed out, “The technical specification document Miru provided to the CENI (Congo Election Commission) also includes several explanatory graphics and more detailed information about the company’s software. The images show various ports on the side of the device for USB flash drives, used to activate machines, as well as ports for ethernet networks and an SD-card memory slot. The document further references 2G and 3G wireless cellular connections, and specifies reliance on an outdated version of an Android mobile operating system from 2014.”

Hall continued: “Without taking precautions to carefully monitor, control and clearly distinguish Miru’s USB flash drives, an outside actor could enter a polling location and easily switch out one or more USB flash drives, potentially changing results or introduce malicious software.” He also emphasized that “relying on 2G and 3G wireless cellular connections could leave information stored on Miru’s system open to tampering via hacking. There are also concerns about using an outdated Android operating system (Android 5.0.2) without security patches to account for serious security vulnerabilities discovered in this software after its 2014 release.”

Nicki Haley, then the US Ambassador to the UN, warned Congo that they should not use the electronic system because it was too easy to hack.

In principle, these discussions are exactly the same discussions that are going on in South Korea today, two months after the April 2020 election. This year, the experts are talking about the LG U+ 5G system and Huawei equipment, which also come with USB ports and transmitters via WIFI. There are signs of anomalies all around, bolstering election fraud allegations, but the NEC refuses to engage in public discussions about them.

In the interest of preserving democracy in South Korea, it is incumbent upon the newly elected 21st National Assembly to look into all the allegations of election fraud and verify that the electoral process had met all the standards of advanced democracies around the world before they embark on any other legislative agenda. Otherwise, the body will carry with them an asterisk next to its name as “a parliament that never was” for years to come.

Source: http://www.skyedaily.com/news/news_spot.html?ID=72753