The article was originally published on The Providence Magazine.

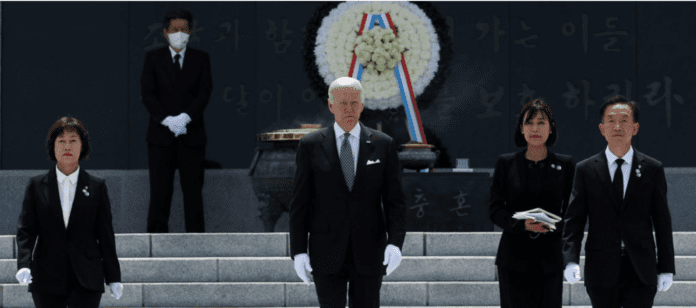

The fact that President Joe Biden chose South Korea as the first stop of his first Asian tour since his inauguration is significant. Washington and Seoul are seeking to upgrade their military alliance into a “comprehensive global strategic alliance.” But they also want to upgrade their economic ties into a “technological alliance,” with the intent of developing technology and supply chain collaboration based on shared values. South Korean President Yoon Seok-yeol described the US–South Korean partnership as an “economic and security” alliance, emphasizing that “economy is security, and security is economy.”

This statement may shed light on the untold dilemma of East Asian countries in recent years.

These countries’ security depends on the United States, and their economies on China. Over the past two decades, most East Asian countries have struggled to maneuver between these two superpowers. This has been true for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries as well as for Japan and South Korea, which have always had close military alliances with the United States. Singapore is also a leading advocate of a balanced diplomatic relationship between China and the United States. In his book Hard Truths to Keep Singapore Going, Lee Kuan Yew, the late Singaporean prime minister, describes how diminutive Singapore had to struggle to thrive among its powerful neighbors while maneuvering between two global hegemons—China and the US. It was Lee who formulated Singapore’s policy to “not choose sides between America and China.”

Indeed, there is a pragmatic historical wisdom to the hedging-and-balancing strategy of “economic reliance on China and security reliance on the United States.” However, effectively achieving such a fine balance entails two prerequisites. First, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) must have enlightened, rational leaders who can credibly guarantee that China will “rise peacefully and refrain from any hegemonic aspirations” well into the future. Second, in its dealings with the US and other foreign powers, Beijing must learn to embrace healthy competition based on a market economy and common interests, whereby a CCP-ruled China gradually integrates into a rule-based world order.

A report published by Singapore’s ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute in 2021 shows that although China provided the most financial aid to Southeast Asia during the COVID-19 pandemic, distrust of China has increased in the region. For example, 63 percent of respondents do not trust China to “‘do the right thing’ to contribute to global peace, security, prosperity and governance,” while only 17 percent of respondents are confident that China will “do the right thing.” A majority of respondents deemed that “China’s economic and military power could be used to threaten my country’s interest and sovereignty.” Nearly 90 percent of respondents who regard China as Southeast Asia’s “most influential political and strategic power” worry about China’s political and strategic influence.

Lee, too, was acutely aware of the CCP’s bullying ways. Unlike the United States, which Lee noted does not “force [democracy] down your throat,” the Chinese regime is “not interested whether you run a democracy or you’re despotic. They just want you to comply with their request.” And China can often ensure this outcome just by squeezing other countries economically, leaving them gasping for air.

Even if most East Asian countries are reluctant to choose sides, how long can they sustain the precarious state of “economic reliance on China and security reliance on the United States”? As China transitions from “peaceful rise” to “wolf warrior diplomacy,” and as the competition between Beijing and Washington takes on more and more cold war characteristics, East Asian countries are increasingly stuck between a rock and a hard place.

On the international stage, observers once regarded China as a humble underdog. Today, they perceive the totalitarian state as the neighborhood bully that flaunts its wealth and power. As the CCP becomes a growing economic and security threat to East Asia, the United States is using a new cold war strategy of forging a values-based diplomatic alliance that welcomes East Asian democracies and shuns authoritarian regimes like China and Russia.

If South Korean President Yoon simply chooses to side with the United States, what are his chances of success? He simultaneously faces three favorable conditions and three potential crises.

To read more, click here.